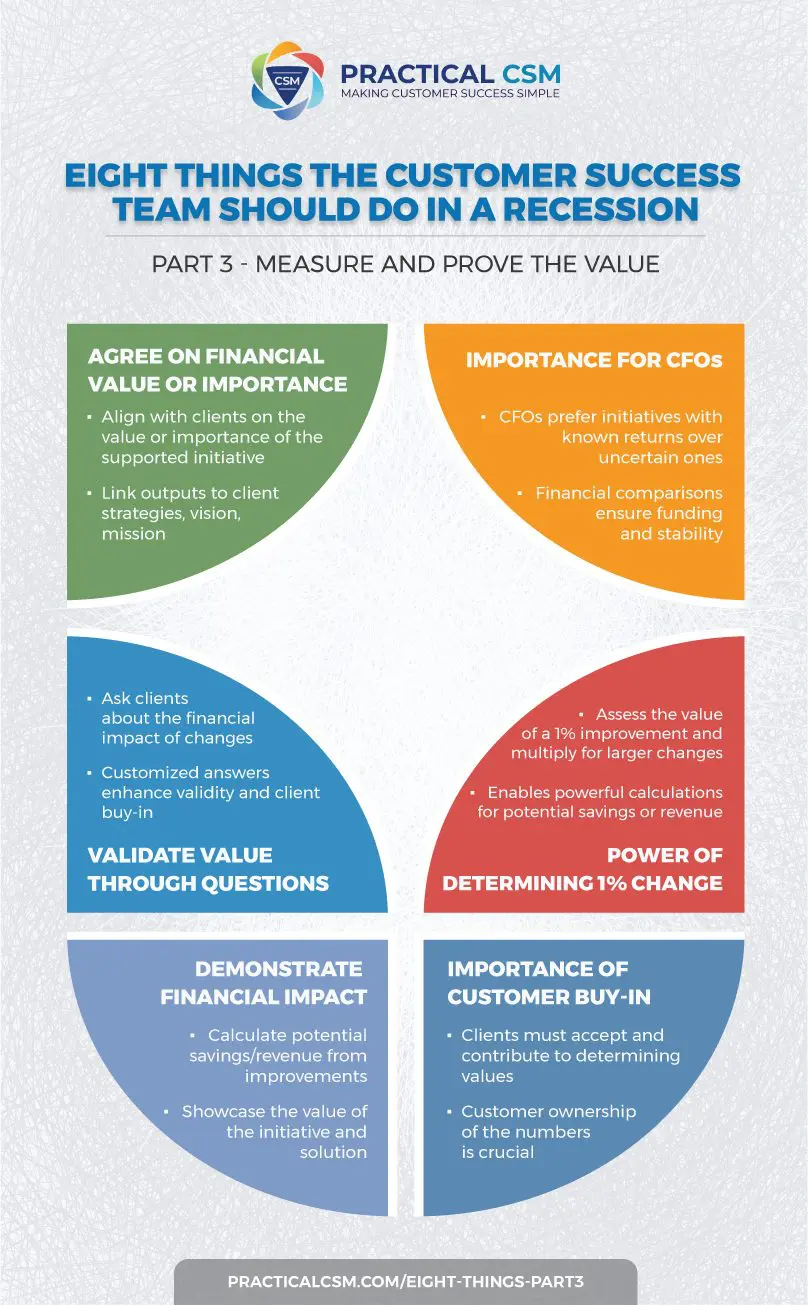

Measure and Prove the Value

Eight Things the Customer Success Team Should Do in a Recession – Part 3

Overview

There were a lot of great points made in my recent interview with Nick Mehta, CEO of Gainsight, but there was one aspect of the interview in particular that I think was particularly important. This was the part of our conversation when we discussed the role of the Customer Success Management team during a recession, or during any period of uncertainty where businesses are tightening up budgets and only performing essential activities due to fear of an impending recession, which I think is a good description for the situation we find ourselves in right now.

This article is partially based upon my recent discussion with Nick Mehta, and describes eight practical steps that almost any Customer Success Management team should be able to take when faced with a recession or period of uncertainty. In fact, to be exactly accurate we will discuss seven things to do and one thing to avoid doing. The original interview that inspired this article was recorded and the recording is available from our website here and from our YouTube channel here.

The eight practical steps we will be covering in this article are:

- Proactively Offer Your Help

- Address Your Client’s Current Priorities

- Measure and Prove the Value

- Use Process to Create Efficiency

- Automate Customer Success Management

- Leverage the Power of Client Communities

- Make Your Product an Essential Need

- Do Not Become the Concierge

Measure and Prove the Value

When it comes to business initiatives, the aspect of measurement that tends to the easiest for our customers to measure and report on is costs. This is because these are well known and documented up front (such as your monthly fees for your SaaS software and the monthly salary costs of the users for example) and/or easily measured as and when they come in (such as the costs of energy consumption). What is sometimes a lot harder is to calculate and report upon the value being created by the initiative in the same way ie in financial terms rather than simply as a stated benefit such as “It makes it easier to perform a certain task” or “It reduces the time taken to complete a certain task” for example.

I am of the strong opinion that this is one way in which CSMs need to improve their game as a general rule. More often than not, we are great at calculating things like activity (for example numbers of logins, numbers and types of features used, number of hours logged in, etc) but very poor at turning that into meaningful results for the client. Those meaningful results might for example be increases in inter-team collaboration, or improved quality of end product, or reduced time to market for new software versions. But even then we are still only halfway, because it is still difficult for someone such as a Chief Financial Officer (CFO) to directly compare the expenditure on the initiative with the income or savings created by the initiative to analyze the overall value being created.

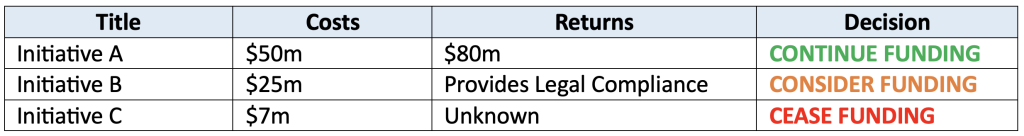

In the example above we see that a CFO might find it easier to agree to continue funding a relatively expensive initiative that is known or preferably even proven to be either bringing in additional revenues or reducing overall costs (net of the costs of the initiative of course), than it would be to continue funding a relatively modestly priced initiative where the returns are unknown. CFOs cannot operate on guesswork. Indeed their entire role is based upon them taking due care to ensure that the company’s finances remain buoyant or at least workable on into the future. How can they do this if they are left to guess at whether a particular initiative is successful or unsuccessful right now and/or in the future?

Of course, not all initiatives are designed to directly create income or reduce expenditure. This is where if at all possible you need to come to an agreement with the client as to the relative financial value (or at least the relative importance) of whatever it is that the initiative your solution supports is creating. The basic principle is that the more you couch the value in financial terms the easier you are making it for the CFO to continue their funding. Where that is not possible, the more you link the outputs (and therefore the ultimately outcomes) from the initiative to the client’s essential strategies and/or core vision and mission the easier it is to justify the cost.

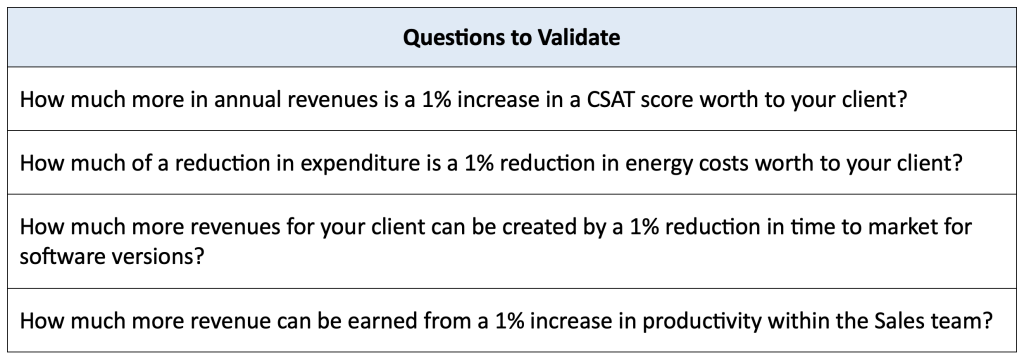

The above questions are examples of the types of questions we might need to ask our customers. Remember that to a great extent it doesn’t matter how we would answer the question, it’s the way they (the client) answers the question that makes it a very important question to ask. By becoming involved in the discussion and by contributing their own thoughts and assistance with developing a meaningful answer, the contributing stakeholder is much more likely to believe in the validity of the answer than the non-contributor will be. Additionally, by contributing their own answer, that answer is now far more customized towards the specific realities of that client than a generic or industry-wide answer would be.

By the way, determining the value of a 1% change can be a very useful start point because of course we can then multiple that meaning by any number to derive the appropriate level of change incurred. So for example if we know that a 1% improvement in production quality leads to a 5% decrease in product returns, and if we know that every product return costs the company $750, and if we also know that currently there were 145,000 product returns last year, then we can start to do some very interesting and powerful math. For example if we can improve production quality by 3%, we will decrease product returns by 15%. Since all product returns costs 145,000 x $750 = around $109m, a 15% reduction would mean an annual saving of a little over $16m. If the cost of the product quality initiative including your solution costs is for example $3m then you should be able to show that the initiative that your solution forms a necessary component of is worth $13m per annum to your customer.

The caveat with all of the above of course, is that if your client’s stakeholders do not accept the values you have attributed to a 1% change then they will not believe the returns you calculate for their initiative. This is why it is essential to get their buy-in and assistance in determining an appropriate and acceptable value. To put it simply, for this approach to work, the customer must own the numbers.

Stay tuned for Part Four of the “Eight Things the Customer Success Team Should Do in a Recession” article which will be published next month.

Go Back to “Eight Things the Customer Success Team Should Do in a Recession – Part One.”

Go Back to “Eight Things the Customer Success Team Should Do in a Recession – Part Two.”

Go Back to “Eight Things the Customer Success Team Should Do in a Recession – Part Four.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.