Value Realization and Performance Management

This article is lifted almost entirely word for word from my company’s upcoming Certified CSM professional training program that launches this summer. More details can be found at https://practicalcsm.com

Problems with Value Realization

A friend of mine who is a senior manager in a customer success role wrote the following in an email to me not so long ago…

“…it’s value realization that is probably the least understood, codified, and the most difficult to get the customer and provider on the same page. I understand each customer may have different and even unique needs and business value they are trying to achieve, however, insights into driving visibility and acceptance of achieving that is paramount.”

And I completely agree with her statement. It is the most important part to get right because as we have said many times, the value realization phase is really the only phase where the customer starts getting anything back from their investment in our solutions). It is also one of the hardest parts to get right. One reason why it’s the most difficult phase for CSMs to engage with is because whereas up until now the work the CSM has done has mostly been about the interaction between the customer’s business initiative and the CSM’s company’s own products and services, the work that needs doing in terms of calculating value being returned has much less to do with the CSM’s company’s products and services and is almost entirely about the relationship and interaction between the customer’s initiative and the customer’s business needs and outcome requirements, and this requires a good understanding of that customer’s unique vision and strategies, business capabilities, and challenges in order to be able to develop meaningful reports on progress towards outcome attainment.

Where does Value Come From?

Every initiative is different in the detail, but there are some commonalities that we can say are going to be true if not for every single initiative then certainly for the vast majority of them. Firstly, we can say that customers will only invest in your company’s solutions if they believe that doing so will be beneficial for them. Of course the details of what that value is will vary widely, but essentially the customer will be using your product or service for some sort of initiative that helps their business in some way. For example, their initiative might be to sell more products or services to their customers, or it might be to make their manufacturing processes more efficient, or it might be to reduce their energy consumption, or it might be to provide better data that helps with business decision making. On the other hand it might be an initiative to help them meet new legislative requirements, or to understand their customers’ needs better, or to improve customer service levels.

The above are some common examples of the types of initiatives that customers tends to have, and what you can probably see quite clearly from these examples and indeed from your own experiences of the types of initiatives that your own customers have and therefore the types of value that your own customers are looking for that value tends to focus around the following key business motivations:

- Revenue Growth (ie selling more stuff to existing customers and/or selling stuff to more new customers)

- Increased Profitability (ie keeping a higher percentage of revenues either by increasing selling prices or decreasing costs)

- Reduced Risk (ie reducing the company’s exposure to potential problems that might negatively impact its revenues or profitability over the long or short term)

From a purely “business financial” perspective (ie if we leave aside any ethical, moral or altruistic principles, and ignoring any personal satisfaction derived from performing a hard day’s work and seeing the results of that work made manifest), pretty much everything a business does is motivated by a desire to improve upon these three aspects of value. Generally speaking, the role of senior decision makers in larger businesses can be pretty much summed up by saying that it is to grow the company’s revenues, increase the company’s profitability and reduce the company’s exposure to risk. That is essentially what they are paid to do, and they do this by developing strategies that utilize the company’s assets and resources (ie its cash, its equipment, its staff, its expertise, its processes, its access to customers, and so on) to best effect in order to do exactly that.

Different companies will have different attitudes towards these three key business motivations. For example, a smaller, younger business might be prepared to take greater risks in order to achieve higher revenue growth and increased profitability than a larger, better established business that would not be prepared to take those risks and which instead develops business strategies that require it to settle for slower revenue growth and profitability increases in exchange for the desired effect of minimizing risk. What we are talking about here of course is corporate strategy, or to be more precise the underlying motivations that will determine what that corporate strategy will be, and which are the same motivations that caused our customer to purchase our products and services in the first place. Hence we have come full circle all the way through the Practical CSM Framework to arrive here at Phase 6: Value Realization, where we now have to tie all the ends together, or rather as a CSM we have to help our customer to tie all its ends together in terms of calculating the value being returned by the initiative so that this value can become known (ie realized).

The role of the CSM during the value realization phase is to enable our customers’ business decision makers to make informed decisions about what they want to do now that they have got this far. Assuming value is being created, that decision might for example be to renew their services contracts with the CSM’s company in order to continue to receive the value that they now know they are receiving. If things are going sufficiently well, it might also be to increase their spending on those products and services or even to adapt some more of their processes and train more of their staff, to enable them to deploy the same or additional products and services in new ways to improve one or more other business capabilities as well.

Of course if the initiative’s milestones are currently not being fully met then their decision might be to take any necessary corrective action to increase the levels of value being returned in order to get them up to the desired level. This might involve the cessation of some activities, increases in other activities and even commencement of new activities. And this of course very aptly describes the process of performance management.

Note that performance management is very important, not just to the customer but also to the CSM, because if performance management is not done well and if therefore either the solution is found to not be helping the customer generate value or even if it might be creating value but that value is not being measured and/or reported on and so is not known about, the customer is more likely to decide not to renew any existing services and not to make further purchases of additional products and or services.

Knowledge therefore is power. Basically, by knowing what is currently happening, the business decision makers will be best placed to decide what needs to happen next. From the CSM’s perspective I would suggest that however things are currently going (ie whether things are going badly, extremely well or merely OK) the CSM should be there to help the customer’s key stakeholders realize what is happening and understand why, and then to formulate plans to rectify any problems and/or increase the value being returned as appropriate. In other words, the CSM should be an influencer on behalf of their own company in the decision making made by the customer’s key stakeholders in terms of helping them to answer the questions “what is currently happening?” and “what (if anything) should we do to improve matters?”.

Two Aspects of Measuring Value: Progress and Financial Returns

Perhaps it would be helpful to think about value as having two quite distinct aspects, and then to apply those different aspects according to the need. We have mentioned these two aspects already, but we haven’t really defined them in detail as yet. These two aspects are Progress towards Outcome Attainment and Financial Returns from the Investment.

Progress towards Outcome Attainment

Customers do things for reasons, or to put it another way, customers have a set of results that they would like to achieve from the investment in money, time and effort that they have already made and are continuing to make in order to select the products and services, implement them, manage their staff through change and ultimately use those products and service son an ongoing basis to actually attain those results. Put simply, if we know the reasons why they do the things they are doing, then we can help them measure and understand the progress towards attaining their desired results, and if we don’t then we can’t. What is more, sometimes even the customer’s own stakeholders do not understand (or at least do not fully understand) their own company’s outcome requirements from the initiative they are meant to be managing.

Where possible then, the CSM’s role is firstly to ensure that everyone knows, understands and agrees on what the customer’s outcome requirements for their initiative actually are, and then secondly to help them measure and report on progress towards the attainment of each outcome over time as the initiative progresses forwards. Ideally the initiative’s stakeholders should select one or more leading indicators to measure, as these are helpful in the early stages of the initiative by providing meaningful information about progress, so that problems can be identified and if necessary amendments can be made to get the initiative quickly back on track in these early stages.

Financial Returns from the Investment

Whenever a business case for expenditure is submitted to the relevant authority for approval, it is unlikely to get approved unless the costs involved in getting the proposed outcomes are clearly and accurately identified in advance. Otherwise it would be like asking the capital investment panel, expenditure committee, CFO or whoever authorizes such expenditures to write an open ended check for as much money as it takes to get the results that the business case is attempting justify the expenditure for. Clearly this is a nonsense, no authorizing authority can possibly agree to an infinite amount of expenditure in order to get a finite return. The risk of failure (ie the risk of the proposed initiative costing the business more than the level of value it returns) would be too high.

Similarly then, once the initiative is under way, and certainly by the end of the initiative (though preferably as soon as possible) the financial returns from the initiative also need to be calculated and regularly reported on, so that the investors in the initiative (ie those who funded it) can directly compare what they are putting into the project with what they are getting back from it. The two problems with this is firstly that it isn’t always very easy to calculate the financial returns from an initiative, since oftentimes not all the value being created is direct (ie financial) value. Secondly, the financial returns do not always start to appear in the early stages of the initiative and are therefore considered to be a lagging rather than a leading indicator, which means that they’re not going to reveal much useful information until late in the initiative, when (for example) it may be too late to make any changes.

Steps in the Performance Management Process

We will start our detailed discussions by thinking about progress tracking first, and return to the concept of financial value later on. Hopefully we are agreed that the details may vary but that essentially the process of value realization in order to gain early indications of progress is an important one, and is one that will remain the same or similar regardless of what exactly “value” might mean for the particular circumstance or situation on which the customer finds itself. Because the detail varies from product to product, from customer to customer, and even from initiative to initiative, the first task in performance management is to determine and clarify what is meant by “value” in the context of the particular initiative we are engaged in. Once this is established, we can then agree how this value could best be measured. Ideally, these two steps in the performance management process should take place early on in the engagement’s planning stages (during Practical CSM Framework Phase 2: Commitment for example).

After the customer has been onboarded and after adoption has been completed, the customer then needs to start using their new or amended capabilities (ie performing activities using the new products or services that the CSM’s company has supplied them with) to generate new or improved outputs. Once this is under way, actual measurements can start to be taken – usually on a routine, regular basis, for example daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc), and of course as soon as measurements start to be collected and recorded, they can start to be analyzed for meaning and that meaning can then be reported to the customer’s managers. Finally, once the managers have been made aware of the performance information, they can decide upon whatever actions they deem necessary (ie to renew services, to make changes, and so on) and then those actions can be carried out. This last part of course is cyclical, in the sense that measurements will continue to be taken, analysis and reporting will continue to occur, further business decision making will continue to occur based upon the new and current situation, and new actions can then be taken based upon these further business decisions.

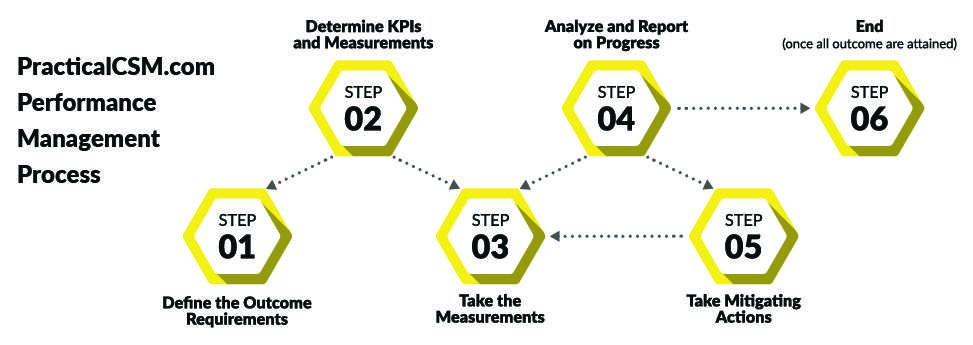

This series of activities might look like this:

Of course the above diagram is fairly simplistic, and for example for some initiatives there may be no “end”, whereas for others (indeed for most initiatives) external and internal influencers will occur to the customer’s business, and this will cause the customer to alter its strategies, which of course will in turn alter their outcome requirements for the initiative. When this occurs the initiative’s goals will get changed to align to the new strategies, and the process of attempting to achieve these new (and usually tougher to achieve) goals will need to start again. From the CSM’s perspective, when this happens it’s all about keeping up with their understanding of the customer’s changing requirements in terms of “business value” and then informing and influencing the customer to make the right decisions regarding renewals of services and purchases of products that will help them to get where they now need to go in terms of their amended strategy in the light of the new influencers acting upon their business from outside and from within.

Changes of this nature may also then lead to the CSM needing to go back to earlier phases of the Practical CSM Framework to help the customer with additional onboarding and adoption requirements that stem from changes to the products and services they have purchased and/or to which business capabilities these products and services are now supporting. Thus as we originally said when we introduced the Practical CSM Framework, the framework itself becomes an ongoing and cyclical tool rather than just a linear and mono-directional one.

How Can I Learn How to Perform These Tasks?

The above is an extract from the Value Realization module within the Certified CSM Professional training program. You can learn how to master these performance management related tasks and much, much more by enrolling in the complete Certified CSM Professional training program. The combination of reading, watching videos, taking quizzes to test your knowledge and participating in case study-based exercises will ensure that CSMs are primed and prepared to assist their customers through the entire CS engagement from initial preparation through to engagement evaluation.

The Certified CSM Professional training program is brand new, and will be launched in the summer of 2019. Please visit us at https://practicalcsm.com for more information.